Don’t buy organic food if you want to seriously address climate change

Steve Savage | Originally posted on Genetic Literacy Project, October 7, 2019

As we approach the 2020s, many consumers have accepted the marketing/activist narrative that organic farming would be the best option for food safety and to mitigate the most damaging effects of climate change. The inconvenient truth is that organic farming is a terrible option from a climate change perspective. Its dependence on manures and compost involves huge, but rarely recognized, greenhouse gas emissions in the form of very potent methane and nitrous oxide.

But perhaps its biggest climate change issue is that organic farms are mostly less productive per unit area than “conventionally” farmed land. With rising food demand driven mostly by rising standards of living in the developing world, there is a need to boost farm production, and that means the very undesirable conversion of forests or grasslands to agriculture in places like Brazil. That leads to major carbon dioxide release from what had been sequestered carbon in the soils, and also the loss of biodiversity and other environmental services provided by those natural lands.

Background on “organic” farming

The organic farming movement started in the late 1800s and early 1900s in response to issues that had arisen in plough-based agriculture, which had converted most of the prairie land in the American Midwest to farmland through the process of sod-busting.

Spurred by the Homestead Act, Americans moved to the Midwest to claim their 640 acres of government land give-away. Most used the new polished steel plow made by the John Deere company to turn what was once a diverse grassland ecosystem into what became one of the most productive agricultural regions in the world. However, the way that these farmers needed to control weeds and make the land suitable for planting was to mechanically disturb the soil, and that lead to the death of many soil organisms and the breakdown of the organic matter that they had made using the energy supplied by the plants that grew there.

Over time, as the soil was degraded by this tillage, it became less fertile, less able to capture and store rainfall and less productive. The common solution was often to move on to “virgin” land and do the same thing to the biome there.

The true innovation of the early organic movement was the realization that for a soil to remain productive over time, the organic matter content of the soil had to be replenished after each crop harvest. The movement’s solution was to import large quantities of organic matter from other sites in the form of the manure or composted manure from the animals fed on those other agricultural acres. This worked, but it was never, nor is it now, a viable solution for US or global agriculture.

Even so, starting with the Rhodale Institute’s publication of “Organic Gardening” magazine in the 1960s and the eventual establishment of a commercial organic industry in the 1970s, the mostly non-farmer consumers in US society were told the story that organic farming was the best way to both feed us and protect the environment.

In 1990, the USDA (US Department of Agriculture) was charged by Congress with establishing a national organic standard to supersede the fragmented certification systems that had evolved to that time. It was a major struggle because the very science-oriented USDA was at odds with the early organic marketers who had focused entirely on the narrative that what is “natural” is always best. The marketers finally prevailed. When the national organic standards were issued in 2002, they were not based on science but rather on the naturalistic fallacy.

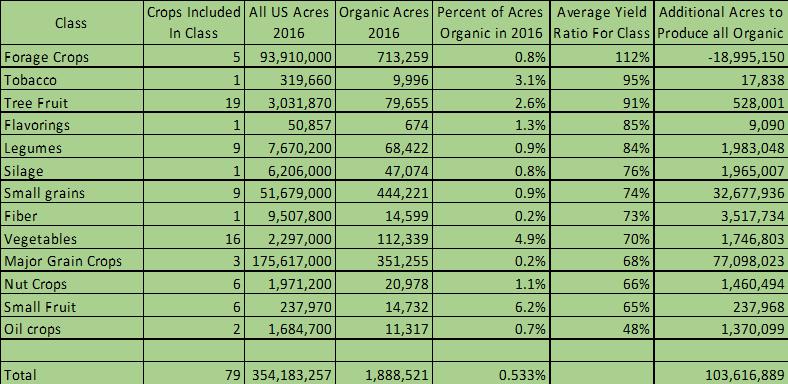

Plant-based protein in an important component of the human and animal diet, but only relatively minor crops like pinto beans and Austrian Winter beans had higher yields as organic crops in the 2016 season. Nearly 2 million additional acres would have been needed to produce these crops as “Only Organic.” This is in spite of the fact that these crops require much less nitrogen fertilization, because they have an association with soil bacteria that fix atmospheric nitrogen for them in trade for energy.

Corn, soybeans and sorghum grown for grain accounted for 50% of all US crop acres in 2016. These crops provide most of the feed and biofuel for the US, as well as many major food ingredients. To have produced these crops as organic would have required 77 million acres to be farmed, something that would drive major land use conversion in places like Brazil and the associated climate and biodiversity impacts of that change.

Small grains are a major part of the human diet. With the exception of the relatively small crop rye, these plants do not yield very well in organic systems. To have supplied the domestic and important global market for these grains as organic would have required 33 million more planted acres, an area comparable to the entire state of Arkansas. Since many of these crops have quality issues associated with where they are grown, there really aren’t places in the US or the rest of the world where this could happen.

The only vegetable crop for which organic yields were higher was sweet potato. Organic represents 4.9% of total vegetable acreage in the US – much more than the overall 0.5% for all crops. Since many vegetable crops do best in specific climatic zones, that significant current organic footprint probably serves to raise overall prices for consumers, even if they do not purchase organic. When that issue is added to the fear of pesticide residues on vegetables driven by the Environmental Working Group’s “Dirty Dozen List,” this only contributes to the missed health advantages of vegetables in the diets of many consumers.

To have produced all the 2016 US grown vegetables as organic would have required 1.75 million more acres to be grown—something clearly not possible.

Tree nuts are considered to be a very healthy component of the diet, and may even reduce overeating that causes obesity because they make consumers feel full. These crops only flourish in certain climates, so there is no possibility that they could all be raised as organic. That transition would require 1.5 million more acres to be dedicated to those crops.

Organic yields of small fruits are often much lower than the national average. This is particularly true for strawberries, cranberries and wild blueberries. The one exception is tame blueberries, mostly in Washington state. To have produced all of this healthy fruit as organic would have required 238,000 more acres, which simply do not exist in areas with a suitable climate. In the case of strawberries, if the 11.6% of that valuable coastal land had been grown conventionally, there would have been 194 million pounds more strawberries available to consumers, probably at a lower price.

Organic makes up 2.61% of the land used to grow tree fruit and grapes. To produce all the fruit as organic would require a half million more acres of land. The organic vs. conventional citrus crop data is complicated by whether the crops are grown in California or Florida, where a devastating invasive bacterial disease has dramatically reduced yields. The best hopes for the future of the California industry depend on mostly non-organic pest control solutions.

Organic Tobacco constitutes 3.1% of the total acreage of this cancer-causing crop. Hops production, which is a booming industry these days for craft beer brewing, is 1.3% organic. Sunflower, which is the most significant crop on this list, is planted on 2.7 million US acres, and an additional 1.1 million acres would be required to produce it as organic.

Most cotton production has shifted to India and other places in Asia and Africa, because it is one of the very few crops grown in those regions with big grower benefits of insect resistance and herbicide tolerance. Still, there are 9.5 million US acres grown and it would take another 1.5 million acres to produce this important fiber crop as organic.

Conclusion

So the good news is that organic remains a tiny part of US agriculture. The not so good news is that for key healthy fruit and vegetable crops, these antiquated farming methods are enough of a factor to raise the prices for even those who don’t buy organic.

Eliminating organic agriculture would not be nearly enough to help with climate change mitigation, but some alternative marketing category that would reward growers who practice the best kind of climate-friendly farming, those who utilize no-till methods and cover crops for instance, could make a real contribution. As consumers, our most climate-responsible buying behavior should be to reject organic and its false narratives.

Steve Savage is a plant pathologist and senior contributor to the GLP. Follow him on Twitter @grapedoc. His Pop Agriculture podcast is available for listening or subscription on iTunes and Google Podcasts.

This article has been adapted from a presentation given by Steve Savage titled Care About Climate Change. Don’t Buy Organic and has been reproduced here with permission.

The GLP featured this article to reflect the diversity of news, opinion and analysis. The viewpoint is the author’s own. The GLP’s goal is to stimulate constructive discourse on challenging science issues.