|

| Wheat harvest on the Palouse in Idaho |

(This post was originally on the Better Food Stories blog 9/26/16)

There is a term in the wine grape industry called “terrior” which celebrates the fact that fruit quality for wine making is greatly influenced by cultivar, climate and soil type. Year-to-year differences in weather further influence the quality of specific “vintages.” Wheat may be a humbler crop, but it is like wine in the sense that there are different classes of wheat for different end-use products and there are different regions where each type excels based on climate (wheat can be hard or soft, spring or winter, red or white, and there is a separate type called “durum” for pasta). There are even year-to-year differences in quality. For instance, to make an artisan bread, it is best to use flour from hard red spring wheat, that comes from the northern plains (North Dakota, Minnesota) or from the prairie provinces of Canada (e.g. Alberta and Saskatchewan). For Asian noodles one wants a soft white winter wheat from the Pacific Northwest. For crackers a soft red winter wheat is best from a place like Southern Illinois or Kentucky. For pasta, a distinct type of wheat called durum is used and this is grown in Arizona and in the northern plains.

There is a term in the wine grape industry called “terrior” which celebrates the fact that fruit quality for wine making is greatly influenced by cultivar, climate and soil type. Year-to-year differences in weather further influence the quality of specific “vintages.” Wheat may be a humbler crop, but it is like wine in the sense that there are different classes of wheat for different end-use products and there are different regions where each type excels based on climate (wheat can be hard or soft, spring or winter, red or white, and there is a separate type called “durum” for pasta). There are even year-to-year differences in quality. For instance, to make an artisan bread, it is best to use flour from hard red spring wheat, that comes from the northern plains (North Dakota, Minnesota) or from the prairie provinces of Canada (e.g. Alberta and Saskatchewan). For Asian noodles one wants a soft white winter wheat from the Pacific Northwest. For crackers a soft red winter wheat is best from a place like Southern Illinois or Kentucky. For pasta, a distinct type of wheat called durum is used and this is grown in Arizona and in the northern plains.

There are several important measures of wheat quality that reflect important properties of the dough, like strength and elasticity. These properties drive features, like how well the dough will rise and balance of different classes of starch, which influence the texture of baked products. A yearly report on U.S. hard red spring wheat examines eight categories of “grading” data and eleven measure of “kernel quality.” 53% of U.S. wheat and 60% of Canadian wheat are exported around the world and purchased by customers looking for specific qualities (based on FAOStats data 2011-13). Europe is a major producer of wheat and has much higher wheat yields compared to the lower rainfall production areas in North America, but European countries still import a great deal of wheat for high quality bread and pasta and use much of their domestic production for animal feed.

As with all crops, wheat is attacked by various pests. Unlike grapes, it is possible to deal with some of the pests by breeding resistant varieties of wheat (winemakers are reluctant to accept new grape varieties preferring the traditional favorites that have been in use for hundreds of years). A key advance in the “Green Revolution” of the 1960s was developing resistance to a particularly damaging fungal disease called “Stem Rust.” That resistance held up for decades, but in 1999 a strain of the fungus overcame the trait, and since then wheat breeders worldwide have worked to breed a new resistance gene into all the different genetic backgrounds for the diverse wheats grown around the world.

In wet climates, wheat can be infected by many different fungal pathogens and commercial production requires the use of several protective fungicide treatments, starting with seed treatments and spaced throughout the growing season. In drier North America, diseases are not as problematic, but do sometimes require treatments to preserve yield and quality. If it rains during the time when the wheat is flowering, a fungus called Fusarium can infect the crop and wheat has proven to be very difficult to breed for resistance. A well timed fungicide spray can help against this disease, but that is not always possible. This particular fungus can produce a mycotoxin chemical in infected wheat kernels called Deoxynivalenol or DON. It is also called “vomitoxin” because of the effect it has on animals that consume contaminated grain. In our food system, the consumer is well protected from exposure to such toxins, thanks to the care and expense taken on by farmers.

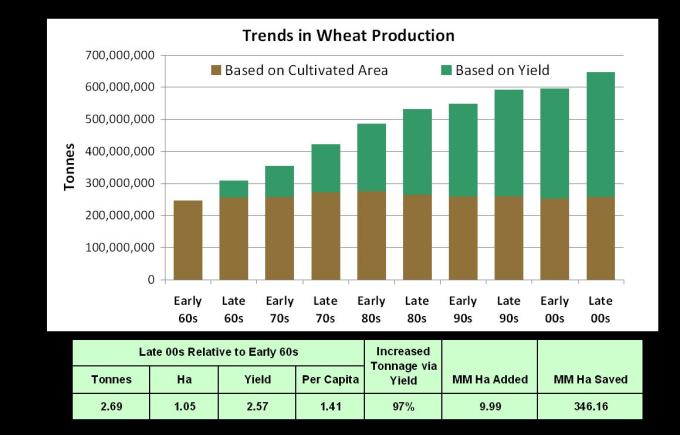

The global wheat industry is really made up of many distinct sub-crops, but as a whole, wheat production has been making steady progress in keeping up with growing global demand with only minimal expansion in planted areas (see graph below). Some of that progress has been made by diminishing pest damage through a combination of breeding and crop protection agents like fungicides. Also, a great deal of modern wheat production is in “no-till” systems where weeds are controlled with herbicides instead of by mechanical tillage. This system greatly reduces soil erosion, lowers fuel use and leads to improved soil health and carbon sequestration.

|

| The green part of each par shows the proportion of the increased production achieved through higher yield rather than additional planting area |