(This post originally appeared on BioFortified on 5/21/11. For links to all my posts on various sites click here)

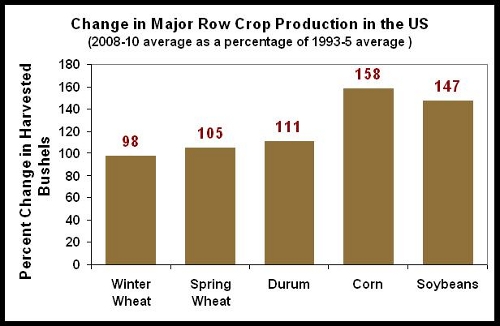

The graph above shows the relative production of these major US row crops comparing the years 1993-1995 (just prior to the introduction of biotechnology enhanced crops) and 2008-10 (the most recent available data which covers a a span which comes 12-15 years after biotech. Soybean production has expanded 47% in this timeframe while corn is up 58% (far more than the quantity now being diverted for biofuel). Both of those crops are predominantly planted to "GMO" varieties, while the various segments of the wheat crop remain non-GMO. Until 2004 it looked as if North American growers would also get to plant biotech wheat, but a vigorous campaign led by GreenPeace succeeded in blocking the technology. Many major European and Japanese grain buyers were concerned about potential consumer push-back (based on GreenPeace efforts), so they made a coordinated threat to boycott all North American wheat exports if any commercial GMO wheat was planted in the US or Canada. This was based on the "precautionary principle."

The wheat industry, particularly the Canadian Wheat Board, asked Monsanto and Syngenta not to go ahead with their plans to sell the improved wheats, and so those often villified companies put their programs on the shelf at the request of their customer base. GreenPeace then declared Victory.

The Traits That Didn't Happen

Monsanto had been developing a "Roundup Ready" version of wheat which would have helped the wheat growers who have grass weed issues. It was also shown to increase yields and it would have aided in conversion to no-till, and increased genetic purity for specialty uses. Syngenta was developing wheat with resistance to a disease called Fusarium Head Scab. That particular fungus is difficult to control with fungicide sprays, but it can severely hurt yields, and it can diminish the value of what grain is harvested by contaminating it with the mycotoxin, DON or "vomitoxin." A major reason that farmers include less wheat in their crop rotations than would be optimal is because of the risks associated with this disease. The fact that these traits would have increased grower income and reduced a dangerous toxin in the food supply were listed in the GreenPeace internal literature of the day, not as "pros," but as "campaigning challenges."

What The Farmers Thought

In the late 1990s, I had the opportunity to sit down with dozens of wheat farmers in Kansas, North Dakota, Minnesota, Indiana and Kentucky to talk about these coming traits. These growers had experience with GMO soy and corn and were very much looking forward to these new products. I was testing various "business models" for how the traits would be made available because, like soybeans, much of the wheat crop is planted with "Farmer Saved Seed."

With non-hybrid crops, farmers have the option to simply save some of their previous grain harvest to use as seed. Typically they buy new, "certified" seed every few years. With Soybeans, Monsanto took the risky and controversial step of getting growers to sign a "technology agreement" in which they promised not to save the biotech seed but rather to purchase it new every year. I, and many in the industry doubted that growers would be willing to do this or that the system could be enforced well enough to prevent free-loaders. After a few, high-profile lawsuits, the new system was widely accepted and no mainstream soybean farmer even questions it today.

Much More Was Lost Beyond The Traits

Before biotech, the soybean seed industry existed mainly as a "price of doing business" for corn seed companies. Much of the breeding advancement was still happening in Universities (though with precarious funding). When soybeans became an every-year purchase, the overall investment in the improvement of that crop went up dramatically. This helped extend the range of the crop into colder Northern regions and dryer Western areas. We are also now beginning to see the pay-off of the investment in genomics and Marker Assisted Selection - biotechnology enabled updates on "traditional breeding." Roundup Ready soybeans were not a "yield trait" as such, but they were far more convenient for busy farmers and easier to "no-till" farm. So now both soybeans and corn had become much more attractive options for farmers, and in many regions the "loser" has been wheat.

The Wheat That Was Not To Be

The expansion of corn and soy production in the first chart represents a combination of factors. Growers planted more of their land to those crops, often using their better fields. They often grew these crops with greater inputs of fertilizer, water because the economic risk was smaller. In most areas there was a distinct change in the long term trends for these crops that corresponds to the pre-biotech era (before 1996) and the post-biotech era (after 1996).

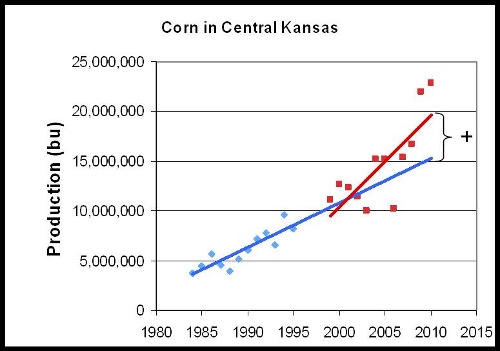

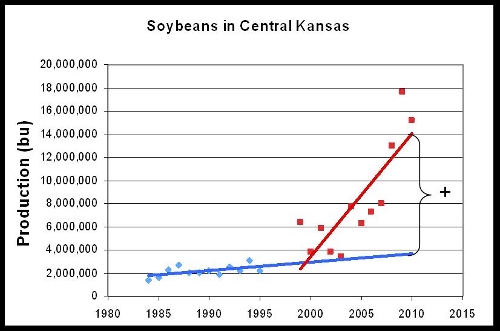

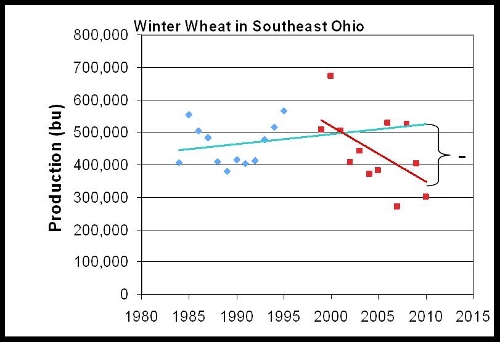

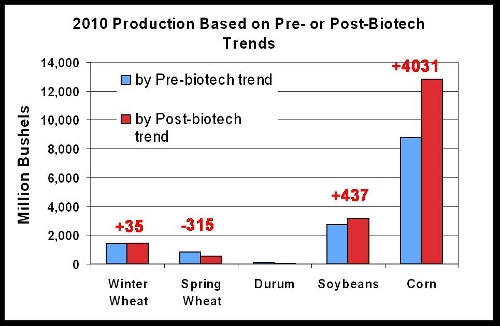

One way to calculate the real "cost" of the GreenPeace wheat victory is to extrapolate what would have been the production of wheat if the earlier trend lines are extrapolated to 2010. To do this I took the data from the USDA-NASS at the Crop Reporting District level (usually 9 districts per state) from the years 1984 to 2010. This allowed me to fit lines for each crop/district covering the Pre-biotech years of 1984-1995 and then a similar 12 year time frame from 1999-2010 as a Post-biotech era. By comparing what level of production each trend for predicted for 2010, the impact of the non-biotech nature of wheat in a biotech world could be estimated. Example trend comparisons are shown below for single district examples of corn, soybeans and winter wheat. Finally those differences are summed for all the districts where data is available over the 27-year time span (238 for corn, 173 for soybeans, 191 for winter wheat, 39 for spring wheat and 6 for durum wheat).

An example of one of many areas where corn productivity increased faster after the introduction of biotechnology through a combination of more acreage being planted and yield progress increasing.

An example of one of many areas where corn productivity increased faster after the introduction of biotechnology through a combination of more acreage being planted and yield progress increasing.A very typical example of an area where farmers began to plant a great deal more soy when it was improved through biotechnology.

An example of an area where wheat planting and intensity dropped in the biotech era relative to earlier trends.

Many Variables but Major Overall Outcomes

Exactly how trends changed for each crop and region varied widely, but in very few cases did the pre-biotech trend continue unchanged. For every crop some areas were up and some down, but the net effect was an overall shrinkage of US wheat production at a time when global wheat demand is constantly increasing. The chart below shows that the biotechnology enhanced crop options saw substantial production increases vs earlier trends, + 437 million bushels/year for soy and a whopping + 4.03 billion bushels for corn. Winter wheat overall declined slower than it had prior to biotechnology for a net trend change of +35 million bushels. Spring wheat, which was much more in the geographic path and time of year of the soy and corn "locomotives," lost 315 million bushels of "potential" production.

Would Things Have Been Different With Biotech Wheat?

Would that have been different if GreenPeace didn't "win?" It is difficult to know because there were other factors in that time frame such as the Freedom to Farm Act of 1996which changed the nature of government crop subsidies and set-aside programs. Delays in biotech trait approvals for import to the EU and Japan altered global market dynamics as did the wide-spread pirating of Roundup Ready soybeans by South American farmers.

Would Monsanto and Syngenta have cross-licensed their wheat traits to allow an attractive package for farmers? Would the transition away from a "saved seed" market for wheat have offset the declining public breeding support which continues even today? It is impossible to know, but the wheat industry has now decided that they don't want to be denied a technological advantage again. National wheat grower associations in theUS, Canada and Australia agreed to a simultaneous launch of any future GMO wheat so that the Europeans and Japanese could not blackmail them again. Even so, it is likely to be at least a decade until that happens because the other thing that was lost in 2004 was the continuous years of breeding effort that it takes to incorporate a biotech trait in the complex world of wheat (winter, spring, red, white, hard, soft.....).

How Much Lost Wheat Is That?

The theoretical 315 million bushels of wheat not being produced as of 2010 represents 8.6 million metric tons (in the units of global trade). That is roughly equivalent to the crop in each of the wheat producing countries Argentina, Egypt, or Italy. It is more than the total wheat imports that go to each of these major, net wheat importing countries (Japan 5.8MMt, Algeria 6.9MMt, Egypt 8.3MMt, Italy 5.4 MMt, Indonesia 4.5 MMt, Brazil 6 MMt, Iran 5.2 MMt).

Putting This In The Context Of The Current Global Food Price Spike

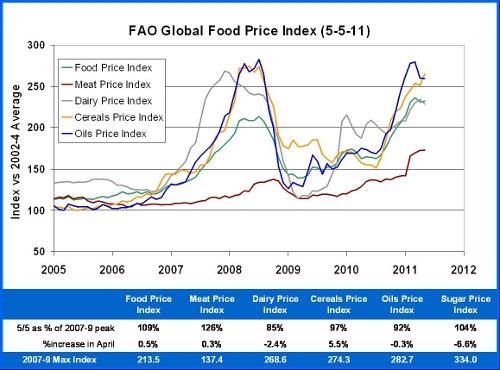

We just finished seeing a severe spike in prices on the global food trade scene in 2007/8 and a new spike is underway and appears to be continuing - particularly for cereals like wheat which is now within 3% of the previous record (see chart below). India is considering a wheat export ban this year. Global wheat demand is expected to double by 2050.

.

Then, just to add insult to injury, the US congress cut funding for the Global Wheat Genomics Center at Kansas State . That happens as a new strain of the dreaded Wheat Stem Rust pathogen is threatening wheat crops in more countries every year.

We probably won't ever be able to make up for what has been lost for one of the world's most important human food crops. The catch-up on biotechnology will not be in time to help many poor people survive or to prevent the political instability implications of food shortages. These are the true "Costs of Precaution," but they will not be borne by the GreenPeace activists in rich nations. These very real costs will be borne by poor families in places where wheat can't be successfully grown. GreenPeace was happy to take credit for stopping this technology. I wonder if they are willing to take credit for these consequences.

Norm Borlaug said: "If you desire peace, cultivate justice, but at the same time cultivate the fields to produce more bread; otherwise there will be no peace."

I'd go with Norm's "Peace" agenda, not that of GreenPeace.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please send comments if you wish. Sorry about the word verification, but I'm getting tons of spam comments