|

| The Tardis (photo by Zir, Wikimedia Commons) |

The show has been running on the BBC since 1963, and part of

what makes that long run possible is that the Doctor has the ability to be

re-born from time to time with a different human body (although supposedly with

two hearts). There have been 13

different stars playing the part of The Doctor, and the most recent one is

Jodie Whittaker (#13), the first female. I just finished binge watching that

season to catch up! Other recent leads have been David Tennant (#10), Matt

Smith (#11), and Peter Capaldi (#12).

Hard core Doctor Who fans call themselves “Whovians,” The

Urban dictionary puts it this way: “A few easy

ways to tell if someone is a Whovian are: Turn off all the lights while

repeating "Hey, who turned out the lights?", moving statues around

while they aren't looking or telling them not to blink while staring at a statue, yelling exterminate at them in a freaky as hell robot voice, and watching

how they react. If they start screaming they're most likely a Whovian.”

So, what’s the “exterminate” thing about? There are new and different “bad guys” for

the Doctor to out-wit in most episodes, but throughout the years of shows, a

frequent “threat to the future of humanity” has been a strange race of robotic

space beings called the Daleks. Back in

the earliest, obviously low budget days of the show, the Daleks looked a lot

like modified trash cans (I guess “dust bins” since it’s British) with toilet

plungers for arms. That basic, funky,

Daleck look has been preserved over the history of the show as has that creepy

chant that of theirs: “Exterminate!

Exterminate! ….”

![Dalek image by Nelo Hotsuma from Rockwall [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b0bf627f2e6b1aad42be49d/1568895307292-RJVTB62BY64OH23FX2JR/ke17ZwdGBToddI8pDm48kL3VKmwKI3leYB51VJjLFB8UqsxRUqqbr1mOJYKfIPR7LoDQ9mXPOjoJoqy81S2I8N_N4V1vUb5AoIIIbLZhVYxCRW4BPu10St3TBAUQYVKcgK5SGg9Ovb1yloBBOHcruw_mYLfAhRzzgArFCB07Dw0L8n4JypuoE5Tg6Wg5Oyvs/Dalek.jpg?format=2500w) |

| Dalek image by Nelo Hotsuma from Rockwall [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)] |

So the Daleks of Dr. Who are a classic example of fictional,

pop-culture aliens who are out to exterminate humans. There are also many

examples of pop-culture stories of humans trying to “exterminate” some sort of

alien invaders. On today’s

POPagriculture podcast we are going to talk about a real world story

about how humans successfully managed to “Exterminate” some alien invaders who

were threatening the grape industries of California.

Standard Intro

So, in California there are lots of farmers who tend 880,000

acres of grapes. These include those

that are specifically for drying to make raisins. Other grapes are grown as a nice, fresh,

mostly seedless snack. Throughout the

state there are also various “appellations” for wine grape production. Together these crops bring in about 5.8 billion dollars a year to

the state’s economy. These products are loved by not just Americans but by

people around the world. California has nearly

ideal climatic conditions for each of these grape categories, and since they

are relatively drought tolerant they are a good fit for our limited water

resources. One nice thing is that we

don’t have much rain during the summer and so we don’t have to deal with some

difficult fungal diseases that are a big challenge in places like Europe. There are still certainly pests that have to

be dealt with, but the grape industry has always been a leader in doing that is

a sustainable

way.

|

| Lobesia: European Grapevine Moth image by Jack Kelly Clark, University of California Extension |

So that’s the background, but the drama for our story began

in the summer of 2009 in a famous, premium wine grape-growing region called the

Napa Valley. One of the growers there

spotted a caterpillar munching away on some of his grapes. Now there are several kinds of moths that can

be pests of California grapes, particularly during their larval stage as

caterpillars. But the grower noticed

that this one didn’t look like those familiar types. Being suspicious he sent a

picture to a county extension agent – a kind of University employee whose job

it is to support the industry with research and advice. It turned out that was a new kind of moth to

California – an alien invader! Ok, not a

space alien, but scary from the perspective of grape farmers. It was called the European

Grapevine Moth or “EVGM.” As its name implies it has been a pest in that

continent for a long time. That name doesn’t

sound scary enough for our story so lets use the scientific name, Lobesia botrana.

Now the thing is that this wasn’t

just another moth. The caterpillar stage

of this bug would do a lot more damage to the grape clusters than the other

moth species and that would mean nice things like “frass” or insect poop on the

grapes or later the raisins. To make

matters worse, the feeding opens the way for fungi that rot the grapes and that

kind of infection can spread from berry to berry throughout the cluster. This would make it a lot harder for the

raisin growers to have a high quality product, it would mean a lot more food

waste even all the way to the consumer level for the table grapes. Moldy grapes definitely don’t make for high

quality wine!

|

| Rotting grape image by Andrea Lucchi, University of California |

Now of course there wasn’t an

extraterrestrial “Doctor” to lead this campaign, but even Dr. Who drafts a team

of regular humans to help defeat the aliens.

In this case the team comprised

representatives of the grower communities, university experts and government employees

from the relevant state and federal departments. They held an emergency meeting

and decided that they wanted to see if they could come up with a way to not

only stop the spread of the pest, but if at all possible to completely

eradicate it from California. Eradicate!

Doesn’t sound quite as harsh as “exterminate!” but it’s essentially the same idea.

In order to see what they were up

against, sixty thousand “Sticky traps” were distributed state wide at a density

of 39 per square kilometer in vineyards and 10 per square kilometer in

residential areas. In the next 2010 growing season they found 100,000 moths in

several California counties. This was

going to be a big challenge! Only a

comprehensive strategy with broad participation would give any hope of

winning. So the team developed a multi-prong

strategy:

Those sticky traps continued to be

used to monitor progress, but they were careful to use red colored traps

because they are much less likely to accidentally trap honeybees.

It was important to find ways to

limit further spread of the aliens. The adult moths can fly, but they don’t

tend to fly too far as long as they can find the grapes they want. Quarantine

rules were set up to prevent fruit, farm equipment, recycled fence or grape

posts, or other things that might allow the pest to hitch-hike long distances. It

turned out that the moth larvae could survive the stemming and crushing and

even pressing of wine grapes – so it was critical not to move around those

by-products of the winemaking process.

They also used an approach called

“pheromone confusion” that was set up on an area-wide basis where the Lobesia had been found. This involves putting up emitters of the

specific sex hormone for this moth so that the males are getting so many “scent

trails” that they rarely actually find a female to actually mate.

There were lots of outreach

programs to get everybody up to speed on the situation and to know their

role. This included grape growers,

wineries, and fruit or raisin packers, and pest control advisors. The outreach

also had to include on the order of 3,000 homeowners because they also needed

to cooperate, especially if they had backyard grapes, as many did. The

coordinated task force would help those owners to treat their grapes or remove

their fruit so that they didn’t become a reservoir to then fan out into the

commercial vineyards. Not only were there public meetings to reach all these

groups, there was a Facebook page and a website at www.bugspot.org.

The researchers developed a

sophisticated “degree day model” to predict when each of the 3-4 new

generations of moths would be coming out so that insecticide sprays could be

timed just right, not only to protect the crop, but to prevent the moth numbers

from really blowing up as they would if not strategically checked this way. Almost all of this spraying was done on a

voluntary basis at the grower’s own cost.

In Napa and Sonoma in 2012 the growers treated more than 12,000 acres. The organic growers also sprayed using the

insecticide options that are allowed under their rules.

The combination of the

quarantines, the pheromone confusion and the well-timed insecticide sprays

achieved what is called an “allee effect” in population biology lingo. This is when the population size gets down to

the point where there are too few of the pests in a given area to successfully

mate.

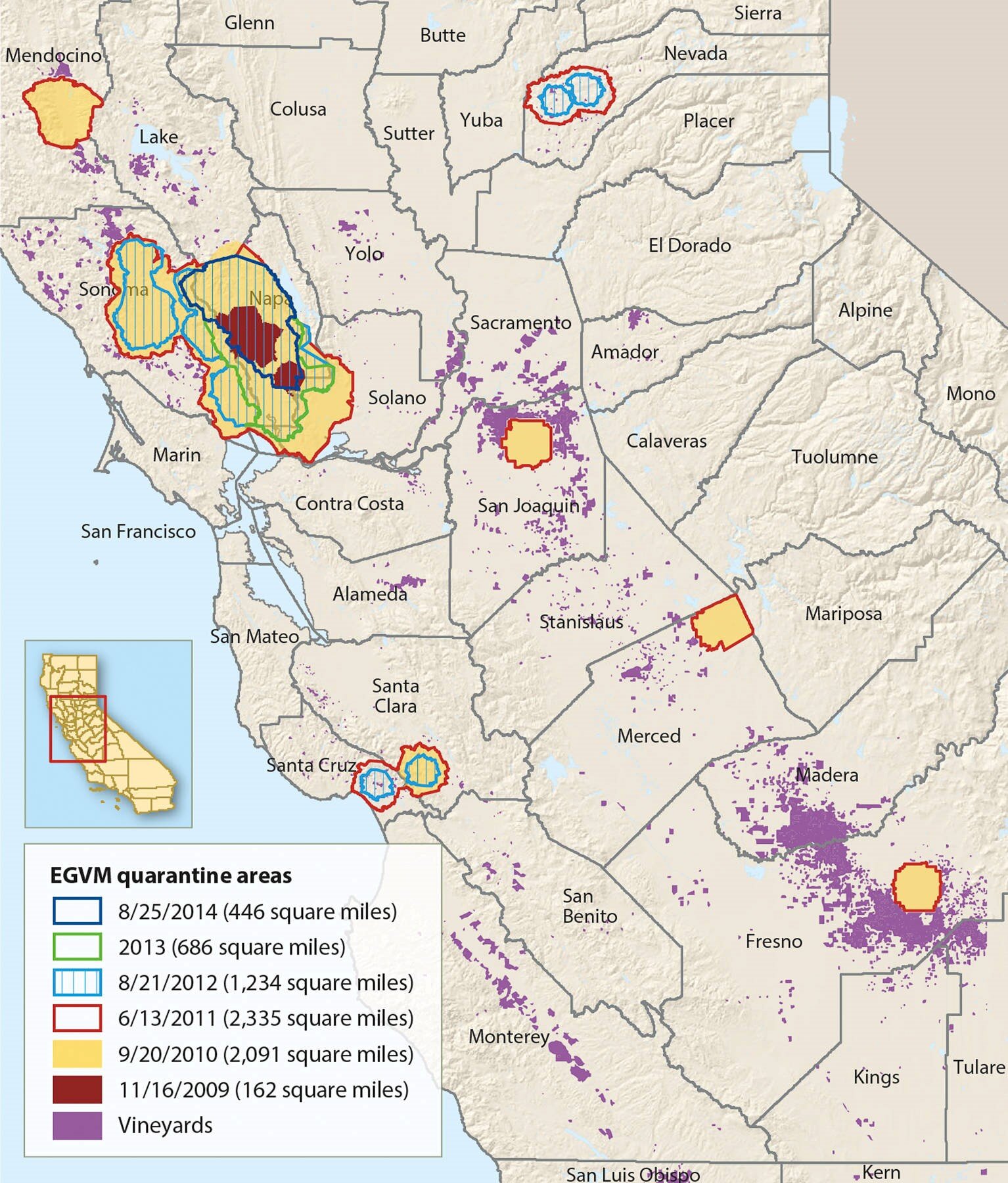

|

| Historical progress towards eradication of EVGM from California. University of California. |

This massive, voluntary,

cooperative effort was highly coordinated across the different counties of the

state and it began to pay off. In 2011

there were 2,335 acres quarantined because of the presence of the moth. By 2014 that number was down to 446 acres. By 2016 the pest was officially declared to

have been eradicated.

|

| Victory Lap! (University of California) |

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please send comments if you wish. Sorry about the word verification, but I'm getting tons of spam comments