(This Blog was originally posted as a Podcast/blog on the POPAgriculture website on 9/5/19)

For some reason, our culture seems to be fascinated by a good murder mystery. I think we all believe that murder is a horrible thing, but we love a story about “good guys” solving a murder case using smarts, careful observation and maybe a little luck. Then we can celebrate when they finally crack the case. “In Cold Blood”, Truman Capote’s book on the 1959 murder of a family in Kansas, played a large role in the growth of the true crime genre. The podcast, Serial, kicked off the most recent true crime renaissance, paving the way for many other true crime podcasts as well as series and documentaries like Netflix’s “Making a Murderer” and HBO’s “The Jinx.” And, who can discount the influence the show “Law & Order” has had, fueling our appetite for stories “ripped from the headlines”? But what about plants? Can they be murdered? Well there certainly are cases where people “murder” plants in a way that is bad, like deforestation.

Image of deforestation

by Vera Kratochvil. Actually this was originally a

pest-based mass murder – bark beetle infestation

(purchased image)

But plants are most

often murdered by other organisms from nature that we call “pests.”

I was originally trained as a “plant pathologist” and we are

the folks who study the diseases of plants. My graduate work was with diseases

of grapes, hence my Twitter handle, @grapedoc. Well, plants, including grapes,

can sometimes mysteriously die. On today’s episode, I want to talk about an alarming new

disease of grapes that arose in the 19th century. It took a long time for scientists to track down the

culprit. For decades, the “murderer” couldn’t be identified and what was

happening in American vineyards really was a case of serial killings whose

trail ran cold. A couple of weeks ago, I had a chance to meet another plant

pathologist who was one of the key “detectives” who finally “cracked the case”

of the mysterious deaths of grapes. He was a player in a great story that I’m

happy to be able to share with you today.

When Europeans began to colonize North America 400+ years

ago, they brought along the crops they knew how to grow so they could have food

– things like wheat, barley, apples, and grapes. Over time, they also adopted

several kinds of plants that were unknown in the “Old World” like potatoes,

tomatoes, corn and blueberries, which

were also taken back to Europe. Back to the settler’s familiar crops - some did

well in the New World, but others didn’t. Wheat did great in the Northern

Colonies, but poorly in the South because of a fungal “rust” disease favored by

the wetter, warmer weather there. The winters in the North were too cold for

one of the European’s favorite crops – grapes. When the settlers tried to grow

grapes in the South they would grow for a while, but then mysteriously die

after a few years.

The Anaheim vineyards would have been

"head-trained" like this rather than the modern system of trellising (Image from UC Davis)

The Spanish brought the first grapes to the New World. The

Friars that set up the first set of missions in what would become California

needed the grapes to make wine for communion. The grapes thrived there because

of the “Mediterranean” type of climate which was much like that of Spain or

Italy or parts of France. For a long time, the grapes did well, but then in the

late 1800s they began to mysteriously die, particularly in the Anaheim area. Of

course, that is a city today and the home of Disneyland, but it started out as

a farming community. There is a newspaper

article about these mysterious

vine deaths that you can see online from “The San Francisco Call” from December

of 1894 about what had come to be called “Anaheim” disease. It describes how

over a period of 10 years the strange malady had ravaged over 20,000 acres of

grapes and nothing the growers did seemed to help. Anaheim has also been the

scene for some human disease incidents, like the 2017 outbreak

of Legionnaire’s disease that was linked to those

who visited Disneyland. But the 1894 article was quoting a talk given by the

head of the State Viticultural Commission, E.C. Biehowsky, in which he was

celebrating the fact that the disease seemed to be abating although no one knew

why. But the case of vine deaths remained unsolved and there were other

outbreaks that killed vines in the

1930s and 1940s. This eventually drove the grape industry out of Southern

California and into other parts of the state.

Back in 1892, California’s

first professional plant pathologist, Newton B. Pierce, tried

to unravel the mystery of this disease. He suspected that it was caused by a

bacterium but he wasn’t able to culture any and use them to replicate the

disease – the protocol called “Koch’s Postulates” that is the required way to

provide proof of what kills or sickens something in the “courtroom” of science.

Others ended up naming this malady “Pierce’s Disease.” That’s not a great

outcome. I hope they never name some deadly plant disease after me!

The next “detective” on

the case was Bill Hewitt at the University of California, Davis. He showed that

the disease could be transmitted from one vine to another by grafting and that,

in nature, the disease was spread by little sap sucking bugs called blue-green sharpshooters.

This fit the M.O. of a virus and that would also explain why you couldn’t

culture it. Suspect #2, a virus. Then, a competing set of detectives in Florida

showed that the disease could be suppressed a

bit with the antibiotic tetracycline. That made them suspect it was a

mycoplasma – effectively the third “suspect” in this case. One of those

researchers at the University of Florida is Don Hopkins and he is the actor

from this story that I recently met. The Florida group’s suspicion about a

mycoplasma was shared by a grapevine virus expert at Davis, named Austin Goheen,

because he showed that heat could also suppress the disease.

Dr. Don Hopkins from the University of Florida (right) and

Sonoma County grape farm advisor Rhonda Smith (left). We spent two days planting the young

grapevines pictured here for a Pierce's Disease biocontrol trial this summer

Now, the classic meme for

a detective show is someone with a magnifying glass. That might be enough

enlargement power for someone working on a homicide case, but the detectives in

the plant murder investigation needed something a lot more powerful. Fortunately,

there was a powerful new investigative tool that was becoming more available called

an electron microscope. The

earliest work on this tool was in the early 1930s

and it became more practical with work at the University of Toronto in 1938.

With this new tool, scientists were able to see far

smaller things than had been possible with even the best light microscopes. A

researcher at Davis in the 1960s and early 70s named S.K. Lowe assisted Goheen

and another scientist named George Nyland, using her skill with the

department’s new electron microscope. With it, they peered inside the grapevine

to see if they could catch the perpetrator of Pierce’s disease in the act. Inside

the plant’s xylem cells – essentially its water plumbing system - they saw

strange, elongated blobs which they decided to call “Rickettsia-like

organisms,” the fourth suspect in the case. They also described it as a

“fastidious bacterium” because it was apparently too picky to let people grow

it on normal culture media. Goheen, Nyland, and Lowe got a paper describing this

new finding accepted for publication in a journal called Phytopathology

on October 3, 1972, but it didn’t actually publish until March of 1973.

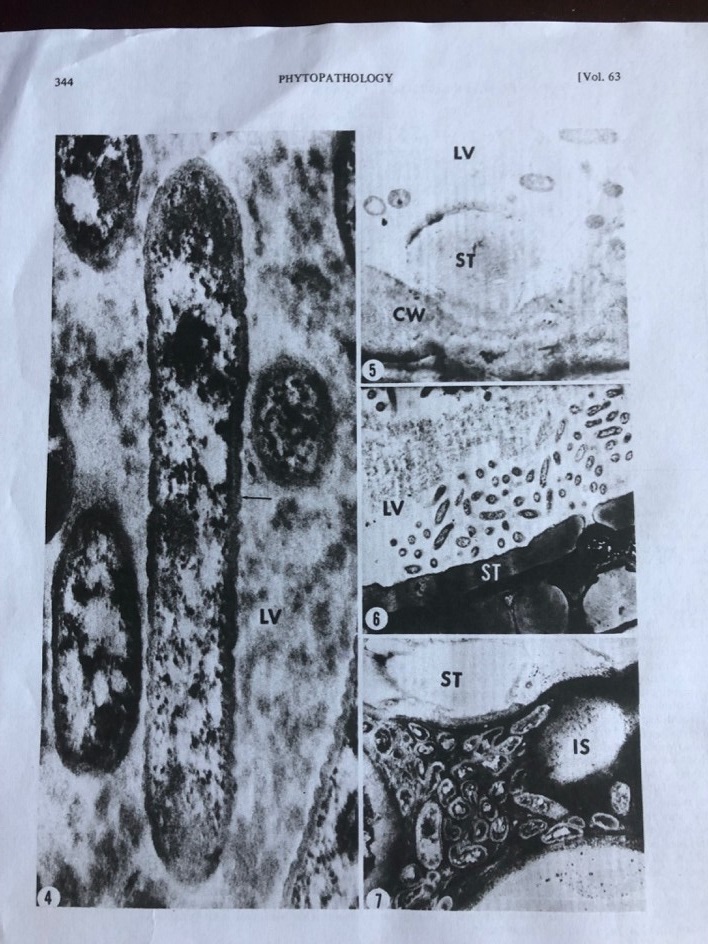

The image of

the "culprit" taken with an electron microscope and published in the

journal Phytopathology

Simultaneously, the

Florida team, Hopkins and Mollenhauer, published similar findings in the

January 1973 issue of the prestigious journal,

“Science,”

also based on what they had been able to see using an electron microscope. They

also classified the suspect as a “Rickettsia-like bacterium.” For both

investigations, those electron microscope images were “the smoking gun.” Even

though these two sets of “detectives” on opposite sides of the country fingered

the same culprit, there was actually somewhat of a rivalry. In a sense, the

Florida team “won” because their verdict came out in print two months earlier! (Remember

this was long before the internet.)

By the time I got to that

UC Davis plant pathology department in the spring of 1977, George Nyland

had

retired, and my new major

professor was the replacement for Bill Hewitt. Austin Goheen was still there

but would retire within two years. Since I was in the “Grape Lab,” I certainly

heard the UC Davis version of the tale of hunting down the culprit for Pierce’s

disease, and they were still just calling it a Rickettsia-like bacterium.

Then in 1978, another team

of scientists/detectives at a different campus of the University of California

in Berkeley finally caught

the culprit red handed by coming up with a

recipe for the medium which would finally coax this picky perpetrator to grow

in their petri plates. These new players were Mike Davis, Alex Davis, and

Sherman Thompson. They found the same organism also caused almond leaf Scorch

disease. So, the “suspect” was now “identified”,

but we still didn’t know exactly what to call it.

It wasn’t until 1987 that

yet another team of six “detectives” used the rapidly advancing tools of

biotechnology and DNA/RNA sequencing to “fingerprint” the grape murdering

bacteria, and they declared it to be a brand

new genus,

which they gave the clever name Xylella fastidiosa: Xylella

for the Xylem of the plant in which it lives, and fastidiosa

in acknowledgement of how challenging it had been to learn to grow it outside

of its unfortunate victims. This diverse team of scientists came from labs at

the USDA, Rutgers, the Weyerhaeuser company, the University

of Illinois, and the Centers for Disease Control, or CDC. Add that to the three

other institutions in this story and you get a sense for how hard it was to fully

understand this disease that had been killing grapes since those early days in

Anaheim, or the even earlier attempts to grow grapes in the American Southeast,

which turns out to be where the bad guys came from in the first place. In the

text version of this episode on popagriculture.com, you can also see

a map of where this bad

bacterium can now be found around the world – mostly in the Americas, but a bit

in Europe and Asia.

It turns out that Xylella

isn’t just guilty of killing grapes. It can cause problems for oaks, citrus,

and the ornamental oleander which is widely used for planting in the median

strips of California highways. Just recently, a new and unique strain of

Xylella showed up in Italy where it “murdered” trees

in venerable old olive groves. I’ve provided a link to a “National

Geographic” article about this – it’s so sad

to think about some of those ancient trees going down. It’s a threat to olives

in Spain and Greece as well.

The tragic

death of an old olive grove, "murdered" by Xylella (Sjor, Wikimedia commons)

|

| A picture I took this summer while flying into Sonoma County. Note the missing (murdered) vines by the river |

But just knowing the true

cause of Pierce’s disease didn’t make the problem go away. You can’t exactly go

out and arrest bacteria that live, as it turns out, in all sorts of plants – cultivated

and wild. What the grape industry had learned was that the bug that spreads

this malady – the blue-green sharpshooter - only likes to live and feed on the

plants that tend to grow along rivers in what are called “riparian habitats.” The

sharpshooters venture out into vineyards from time to time, so the typical

pattern is you see dying vines in the

parts of vineyards closest to the Napa River in Napa county, or the Russian

River in Sonoma county.

There is an aerial photo

above that I recently took while flying into Sonoma.

You see that there are more missing (killed) vines on the side of a vineyard along

the river but not as many near the reservoirs which don’t have a

true “riparian” zone. No one would consider

taking out that natural vegetation in the riparian zone although there can be

state funds to selectively take out certain invasive plants which are actually

even worse than the native ones in terms of being a hiding place for the

bacterium and its vector.

Grape growers in these

regions mostly just deal with a certain degree of vine death because these are

regions with a great reputation for wine quality.

But there is a twist in

our murder mystery! In 1997, there was a dramatic die-off of grapevines in a

relatively new wine grape growing region called the Temecula Valley. This is in

southern California, but further inland than that original problem zone in

Anaheim. Temecula Valley had

not had any problems with Pierce’s disease because it’s pretty much a desert

and does not have those “riparian” zones that the blue-green sharpshooter accomplice

likes. But a few years earlier, probably because of some eggs on nursery stock

imported to California from the southeastern U.S., a new invasive insect had

arrived called the glassy

winged sharpshooter.

The

"accomplice" (Glassywinged Sharpshooter, image from

Now our identified

murderous Xylella

had an accomplice that isn’t at all picky about what plants it feeds on. It’s

happy on citrus and there was a lot of that in Temecula intermixed with the

vineyards. Some of the wineries lost 80 to 90% of their vines in the first few

years of this attack and it seemed like the end of grapes, not just in

Temecula, but potentially throughout the state if that new insect would spread.

The grape industry and its

supporting government agencies quickly mobilized to fight this dangerous new duo.

They found an insecticide that could be given to the roots of the citrus and

grapes through the drip irrigation system. It would then move up and protect

the plant from the sharpshooters. That put the brakes on the epidemic and the

vineyards of Temecula have been successfully replanted and protected. I visited

grape growers in that area in July and they have almost no dead vines and a

thriving tourist industry for wine tasting.

The state also put in

place very rigorous inspections and quarantines of all nursery stock moving

north to prevent the sort of hitchhiking that got the glassy wing here in the

first place. Grape growers all around the state chip in for a state run

monitoring and targeted insecticide program that has, thus far, been able to

prevent that new accomplice from moving to the

rest of the state. It’s working so far, but

no one in the industry is complacent.

The search is on for

additional tools to fight both the insect and the bacterium. It would take

another whole podcast to just list the research efforts, but briefly they

involve ideas ranging from conventional breeding, to biotech traits, to live

biocontrol agents, to insect predators and parasites, to various natural

products, to a new sprayable chemical bactericide. I’m tracking these now and

am even participating in one effort as part of my “day job” as a technology

consultant. I can’t think of anything I’d find more satisfying than to see the

grape industry find a robust set of strategies to shut down that murderous

bacterium once and for all!

Big article Hopkins and

Purcell 2002 – talks about host range, geographic …

HOW I GOT MY LOVER BACK BY POWERFUL SPELL CASTER CALLED DR PADMAN

ReplyDeleteI want to let the world know about Doctor PADMAN the Great spell caster that brought back my husband to me when i thought all hope was lost My husband left me for another woman three months ago and ever since then my life have been filled with pains sorrow and heart break because he was my first love whom i have spent my entire life with,A friend of mine told me he saw some testimonies of a spell caster called PADMAN that he can bring back lover within some few days I contacted him, Doctor PADMAN used his powerful spell to put a smile on my face by bringing back my man with his spell, at first i thought i was dreaming when my husband came back to me on his knees begging me to forgive him and accepted, get your divorce wife or husband back, I will advise you to contact him ,he is there to help you and put a smile on your face HIS EMAIL: padmanlovespell@yahoo.com or info@padmanspell.com Webesit: http://padmanspell.com/ or WhatsApp +19492293867